Thursday marked the passing of Nelson Mandela, South Africa’s former president who spent 27 years in prison and emerged to lead the country out of decades of apartheid. His wisdom, work, and legacy touched many of the Northeastern community. Here, faculty members share their memories and thoughts about Mandela, also known as Madiba.

Margaret Burnham – Professor of law, was appointed by Nelson Mandela to serve on an international human rights commission

From Mandela, Americans grasped the essence of radical leadership: the necessity to stand one’s ground—as when he refused to be released from prison; the duty to negotiate with one’s enemy—as when he met with “the Boers;” the perils and opportunities of governance; the hardships of personal deprivation and the virtues of self-discipline, suffering, and forgiveness; the need to have confidence in oneself and, most importantly, in the ultimate wisdom of the dispossessed, as honed by dialogue, accountability, and contestation. Without his example, America would be a different place today.

Roger Abrams – Professor of law, author of Playing Tough: The World of Politics and Sport

Most people know about Mandela’s brilliant use of South Africa’s victory in the Rugby World Cup as a political tour de force. South Africa’s national rugby team, the Springboks, was beloved by the Afrikaner minority, but Mandela used the “One team, One nation” slogan to unify the country he led as president.

Two other major uses of sport by Mandela and the ANC are also noteworthy. Political prisoners on Robbins Island organized a soccer league and, in this way, honed organization skills that would prove vital when these men eventually became officials in the Mandela government. In addition, the ANC and its allies organized a worldwide boycott of South African sports teams, a set of powerful sanctions that even banned the South Africans from the Olympics.

Sports is a vital lever of political power, something Mandela appreciated more than any other politician of our time.

Dennis Shaughnessy – Executive professor of entrepreneurship and innovation, founder and executive director of the Social Enterprise Institute , which leads unique field research programs in the Dominican Republic, South Africa, and Nicaragua

For each of the past five years, during our SEI field study visits to South Africa, we have met with Madiba’s cellmate, Ahmed Kathrada, and travelled to Robben Island with him to visit Madiba’s cell. For Dr. Kathrada, his most common comment about Madiba is that he fought against discrimination of any kind, but saw the next great battle for both social and economic justice. Blacks in South Africa are free, and no longer discriminated against by those in power, but they remain largely in poverty and without the economic opportunity that must follow freedom in order for true justice to be achieved.

This summer, we also met with Archbishop Desmond Tutu. He articulated the ideals of social justice and equal opportunity that he and Mandela dreamed of for years. With their wisdom in our minds, it’s our job to find innovative ways to create sustainable, productive, and meaningful work for everyone who seeks it. At the end of our visit, the Archbishop shared the words of Mandela with us: “The older I get, the more convinced I am that social equality is the one necessary condition for all human happiness.

Richard O’Bryant – Assistant professor of political science, director of the John D. O’Bryant African-American Institute

Nelson Mandela was the embodiment of all that I think we hope to and like to see in a leader. He impacted me by his example of being strong in his determination to change a system that work so hard against him and his people. He was selfless, strong, committed, principled, and transformative. His life, his work and his servant style of leadership has meant so much to so many. I truly hope that the world remembers him among the greatest leaders the world has ever had.

Gordana Rabrenovic – Associate professor of sociology and education

The influence of Nelson Mandela in championing and practicing forgiveness is enormous. He taught us that, it is hard for individuals and for societies to move on, if they are not able to forgive. Forgiveness is based on our ability to acknowledge that people can be redeemed. At the same time forgiveness does not mean that we forget atrocities that are committed during a conflict. Part of the healing process also means holding culpable actors accountable for their actions during the conflict. As the first president of the new South Africa, Nelson Mandela insisted on building a country based on social justice, inclusion, and forgiveness. This is a legacy that all peoples can build upon for a peaceful future.

Brook Baker – Professor of law, has taught and consulted in South African law schools and clinics since 1997

I will remember Nelson Mandela as a healer of body and soul. I was in South Africa for six months in 1997 while the Truth and Reconciliation hearings were being held. Many of them were broadcast on TV, and I had opportunities to talk with a TRC lead investigator and Commissioner. The stories told by the victims of apartheid were wrenching.Although all the horrific psychic wounds were by no means healed, Mandela’s leadership is establishing the TRC was instrumental in laying the groundwork for partially healing of the national spirit. By 1997, Nelson Mandela had never publicly discussed the emerging HIV/AIDS crisis, even though nearly 5 million South Africans were infected at that time. However, after leaving the presidency, Mandela was instrumental in overcoming the HIV denialism in the ANC. In 2002, he visited the leadership of the Treatment Action Campaign and asked them what needed to be done to fight the scourge of AIDS. Mandela helped launched the public sector HIV/AIDS treatment plan that has grown from zero people on treatment in 2003 to nearly 2.5 million people on treatment today.

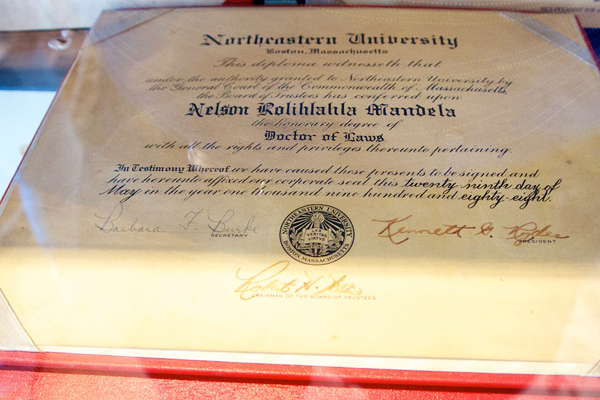

Former South African President Nelson Mandela received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Northeastern University in absentia in May of 1988, while serving his 27-year jail sentence. The degree is currently on display in the Nelson Mandela National Museum in Soweto, South Africa. Photo courtesy of Robert Gittens, vice president for public affairs.