Suqi (Eileen) Wu

Three words encapsulate your Northeastern University experience:

Professional |Collaborative |Opportunity.

What experience has had the most impact on you?

The co-op program and the experiential learning opportunities. I made lots of friends and became a more professional designer because of this experience. I also really enjoy the campus.

Balancing life and school is never easy. What challenges have you faced and what have you learned from them?

Balancing study and work-life during co-op program was incredibly hard. Learning how to manage my schedule and still deliver high quality work was difficult, but these are skills that will benefit me for the rest of my life.

What advice do you have for those considering pursuing a graduate degree?

- Always take action.

- Don’t fear failure.

- If you want something, it’s always worth giving it a try. You are guaranteed to learn something.

How has your experience at Northeastern impacted your ideas about your future?

My enthusiasm for experience design was ignited during my first full-time role at Dr. Panda, an educational app developer. Collaborating closely with the UX team, I witnessed the transformative power of design, driving remarkable sales growth. This motivated my transition to a career in UX design and inspired me to pursue the major I am currently in.

Since being here, I’ve grown my interest in the field of SaaS software design and am growing into a confident designer who not only excels in product design but also takes the lead in driving projects forward in the SaaS software field.

We are all more than our careers or our lives as students. What inspires you beyond your studies?

I have a passion for photography, and over the past two years in Boston, I’ve captured countless moments. It brings joy to my life and helps me appreciate the people around me even more.

The National Association of Educational Procurement and The Northeastern Lab for Inclusive Entrepreneurship Announce Educational and Research Partnership

The National Association of Educational Procurement (NAEP) and the Northeastern Lab for Inclusive Entrepreneurship announced plans to collaborate on a range of research and educational initiatives in support of supplier diversity in higher education to expand access for diverse small businesses to the higher education marketplace.

According to Francesca Grippa, Executive Director of the Lab and CPS’s Associate Dean of Research: “Our collaboration with NAEP reflects a shared commitment to equitable and sustainable procurement practices in higher education, which is a driver of economic growth in our local communities.”

Building on the research conducted by the Lab on ways to expand access for diverse small businesses to the higher education marketplace, the organizations will explore additional areas of research of interest to NAEP member institutions.

NAEP and the Lab will also work together to develop educational resources for both procurement professionals in colleges and universities and diverse small business owners that leverage each organization’s unique programmatic attributes.

“It’s a great pleasure to be able to highlight the impactful academic work taking place at our member institutions coupled with the excellence of their procurement teams. It’s my hope that NAEP’s collaboration with Northeastern can serve as a model for how to bridge the gap between academicians and procurement professionals at our member institutions and bring valuable insights and practices to the procurement community.”

NAEP CEO, Brad Pryba

The collaboration between the National Association of Educational Procurement (NAEP) and the Northeastern Lab for Inclusive Entrepreneurship marks a significant step forward in promoting supplier diversity and equitable procurement practices within higher education. Through joint research initiatives and the development of educational resources, both organizations are committed to fostering an inclusive environment that supports the growth of diverse small businesses and benefits local communities. As this partnership continues to evolve, stay tuned for more updates on our progress and the impact of our collaborative efforts. More to come!

Protected: The Art of AI and Storytelling

A Journalist Reborn

When his industry—and a brilliant career—suddenly collapsed, Ian Thomsen MPS’21 launched a personal reinvention for the digital age

“This is the tale of an old man who dreams of telling a new story.”

So begins Ian Thomsen’s master’s thesis, in which the 2021 College of Professional Studies (CPS) graduate recounts his journey to spectacular professional success—followed by the equally spectacular implosion of his industry and career. Among the most successful sportswriters of his generation, Thomsen saw his working life shattered by the advent of online media and its decimating effect on the print-news industry.

As magazines and newspapers trimmed budgets and staff and his own assignments grew sparse, Thomsen says, “I realized that the page had turned. The instruction manual for a career as I had known it was out of print—in fact, it wasn’t even being printed any longer. I needed to learn the systems of a new era. And the new instruction manual is digital.”

Thomsen became a student of that new manual in 2018, when he enrolled in CPS’s Digital Media graduate program and embarked on a personal reinvention for the digital age. Three years later, with new skills, a new appreciation for interaction with his readers, and a new online newsletter, the self-declared “refugee of the bygone print-media industry” is ready for the next chapter.

Choosing journalism

Thomsen’s rise in what is now often called “traditional” or “legacy” media was nothing short of meteoric. The son of immigrants and the first in his family to attend college, he remembers sitting at the kitchen table at his parents’ home in Mobile, Alabama, circa 1978, working on college applications and discussing career possibilities with his mom. He had written for his high school newspaper, and reporting appealed to him.

“At the time,” he says, “it was the only thing I could think of that I might be qualified to do.”

Thomsen turned out to be very qualified and, as he tells it, very lucky. As an undergraduate at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, he joined the student newspaper. In his junior year, he won an internship on the sports desk at the Boston Globe. That experience would change his life. At the Globe, he found himself working alongside writers whose names had already become legend in the industry—reporters and columnists like Peter Gammons, Bob Ryan, Will McDonough and Leigh Montville.

“They were all so generous,” Thomsen says. “Not only were they the best, but they didn’t act like it.”

For an ambitious young journalist, the internship became a kind of master class.

“I wanted to be a storyteller the way they were,” Thomsen says of his models and mentors. “So, I studied them. Bob Ryan would have a half hour to write his game stories. He’d be writing them during the game, and the colorful analogies and the ways he would describe a play would just create this powerful imagery in your mind.”

But effective journalistic storytelling, Thomsen learned, involved a lot more than just finding strong images. In watching the seasoned writers work, and reading the articles they produced, he realized that it was a process of “training your mind to see something happening, breaking down the elements, moving those elements around, throwing out what was unnecessary and being able to put it back together again to tell a story efficiently, to instantly see a story and reframe facts in a way that someone else might not.”

“I still don’t know if I know how to do that,” Thomsen says. “But I knew they did and I really wanted to learn how to do it.”

When the internship ended, Thomsen applied for a position at the Globe as a staff writer. He got the job, and in his third year at the paper—seven years after that kitchen-table conversation with his mom—an article he had written on the death of a high school football player in a small Pennsylvania coal mining town was named national sports story of the year by the Associated Press Sports Editors. After that, more doors began to open.

‘The best job in the business’

Thomsen spent six years at the Globe, honing his skills and style on story after story of games and events that would enter sports lore. He wrote about Doug Flutie’s famous 1984 Hail Mary touchdown pass, about the epic 1986 World Series clash between the New York Mets and the Boston Red Sox, about two Super Bowls, all three of the Magic Johnson-Larry Bird NBA Finals, and the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul, South Korea. He loved the work. But he didn’t see a clear path to advancement—writers and editors at the Globe, he says, tended to stay at their jobs for decades—so he began to look for new opportunities.

After a stint at the innovative but short-lived The National Sports Daily, Thomsen landed at The International Herald Tribune, a position he says colleagues have agreed may have been “the best job that ever existed in the business [of sportswriting].” Based in Paris, where Thomsen lived with his wife and soon a daughter, and then in London, where his son was born, the job essentially meant he could write about whatever he wanted, wherever he wanted. The freedom was ideal, but it also carried a certain amount of pressure.

“I remember being very scared of it,” Thomsen says, “because I was going to be writing a lot about things I didn’t know anything about such as soccer and rugby and all these other things I hadn’t covered.”

His nerves soon settled, and before long he was covering continental contests such as cricket, soccer and rugby with panache. He also wrote about sports he knew better, like tennis at the French Open and Wimbledon, basketball in the European leagues, and international track and field—along with U.S. stories that echoed around the world, such as the Tonya Harding-Nancy Kerrigan figure-skating scandal.

In conversations with the Herald Tribune’s executive editor, John Vinocur (now a Wall Street Journal columnist), Thomsen also learned a lesson he applied later, when he began his studies at Northeastern: “John said, ‘What you want to do is write a story so that people who know nothing about rugby will be able to read it and understand it and be inspired by it—but then also people who know everything about rugby will be able to read it and like it and be inspired by it.’ You have to try to find a universal element to every story that would cut across culture or language or perspective or expertise. It’s a really hard thing to pull off. But when you force yourself to think like that every single time, it really trains you.”

In 1997, Thomsen landed a job at the era’s pinnacle of sports writing: Sports Illustrated. For someone with his training and aspirations, it was a dream come true. The magazine had built its reputation on taking sports seriously—publishing deeply reported, long-form articles that went beyond scores and sensationalism into the personalities and narrative arcs of teams and individual athletes. Those were exactly the kinds of stories Thomsen wanted to tell, and he wrote them at Sports Illustrated for 17 years. Many ended up on the cover. He started out reporting on European events—the 1998 World Cup in France was one—but soon was spending most of his time on the basketball beat in the U.S., where he reveled in becoming an NBA insider, getting to know players and coaches and writing about a game he loves (although also one, he notes, that despite his passion and 6-foot-6-inch frame, he has never really played).

It was during Thomsen’s years at Sports Illustrated that the digital tide began to rise and print publications of all kinds began to founder. In 2000, Google Ads went online. In 2006, Facebook opened its membership to the public. Twitter launched the same year. Between 2008 and 2014, according to the Pew Research Center, 24,000 newsroom jobs were lost in the U.S. By 2020, an additional 5,000 were gone. From 2008 to 2019, according to Statistica.com, aggregate yearly revenue of U.S. periodical publishers fell from about $42.5 billion to about $26.2 billion. In a related article, USA Today concluded that such figures “illustrate how the press is staggering as it continues its quest for financial sustainability in the digital age.”

Sports Illustrated was no exception. In 2014, Thomsen was laid off, along with eight of his colleagues.

“I could see it coming,” he says. “The industry was dying.”

Ian Thomsen 2.0

In the years that followed, Thomsen worked as a special contributor to NBA.com, taught a Sports Journalism class at Boston University, and wrote a critically acclaimed book on LeBron James, published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, called The Soul of Basketball. But when he was laid off again in 2017, this time by NBA.com, he realized that using the same old tools to repair his professional prospects just wasn’t going to work.

“My story was representative of what happened to many journalists in the print media industry,” Thomsen wrote in his master’s thesis. “I was left with two takeaways. The first was a feeling of vulnerability, as though after a successful career the ground had vanished under my feet. The second was a new sense of mission and purpose to reinvent myself.”

Thomsen’s exploration of the digital universe started in the communications office at Northeastern. In August of 2018, he accepted a job writing for News@Northeastern. A month later, he was enrolled as a Digital Media student in the College of Professional Studies. Soon he was learning an entirely new playbook—one that involved search engine optimization, digital strategy, interactive marketing, branding research, and techniques for harnessing the power of social media.

“Getting a digital media degree at Northeastern,” Thomsen says, “was basically to learn everything I didn’t know anything about and that I had not been trained to understand. In my old world, the print-media world, it was a one-way street. You would write something, and it would be printed, and there was no back-and-forth with the reader. Now, everything depends on that back-and-forth. So there was a lot for me to learn.”

As an older student, Thomsen says he was at first a little self-conscious—but as he got to know his classmates, the feeling soon passed.

“I was by far the oldest person in every class,” he says. “But everything felt perfectly equitable. All of my classmates were just very welcoming and generous. After my initial uncertainty, we were all just students in the class trying to figure it out.”

According to Professor James Gardner, who advised Thomsen on his thesis and with whom Thomsen took “Social Media and Brand Strategy Implementation,” Thomsen’s many years of practical experience simply meant he brought another critical lens to the class.

“Ian has seen the arc of traditional media from its complete and utter heyday,” Gardner says. “He was at the pinnacle of the pinnacle. And then obviously he saw it go sideways as digital disrupted the world of print publications. A lot of my students are young enough that they don’t really have a recollection of how things used to be in a non-streaming entertainment world. It makes it challenging for them to appreciate just how significant that change was. We talked about that in the class a lot.”

Thomsen also became a sought-after partner for group projects and exercises.

“He was in a position to bring a lot of value to discussions around things like storytelling in content marketing—which is a big part of what we talk about in the course,” Gardner says. “You’re not going to find someone that knows more about storytelling than Ian.”

That knowledge, in fact, became the seed for Thomsen’s master’s thesis—and for his current extracurricular venture: a sports newsletter with a twist.

The Word of Eugene

While his day-job at Northeastern remains his primary focus, Thomsen has carried forward an idea that germinated in his thesis work with Gardner. To breathe life into it, he decided he needed an unconventional approach. So, he invented an alter-ego.

“Eugene is a fictional character,” Thomsen says of his newsletter’s narrator. “And he’s going to start out as a bit of a mystery. He’s the father to a large number of kids that he and his wife are raising, so he doesn’t have a lot of time on his hands. And he doesn’t suffer fools gladly.”

In part from a sense of paternal responsibility and in part simply to have his say, Eugene has invented a religion—based on sports.

“He sees this very polarized world,” Thomsen says of his creation, “and sees that sports actually should serve as a model for fixing our world.”

In the blunt voice of Eugene, Thomsen writes a weekly column celebrating the best aspects of humanity. He applies the sports news of the day to lessons of selflessness and teamwork—the kinds of things preached by coaches everywhere.

“Sports is a window,” Thomsen says. “It’s a window into the imagination of people, the inspiration, the ambition—and to building communities. If you’re playing a team sport, you have to build a community, because you have to work with your teammates. If you are pursuing something for yourself, but doing it at the expense of others, you’re making the world worse. But if you’re trying to build a sense of teamwork, and fulfilling yourself in a way that helps others fulfill themselves, then you’re making the world a better place. That’s Eugene’s message.”

Leavening that message is material gathered in the course of Thomsen’s first career—anecdotes and insight from his decades on the sports beat. Using the digital tools he acquired at CPS—many of which he also uses at work daily—Thomsen’s goal is to make the hard-won lessons of a successful print journalist relevant in the age of Facebook, Twitter, streaming games and online news.

If anyone can do it, Gardner says, it’s Thomsen.

“As long as he consistently delivers high quality content,” Gardner says, “I can imagine his subscription audience growing—which in some ways is a very elegant solution. It could become like a flywheel, where the audience loves what he’s doing so much that the audience grows, and the conversion of non-paying subscribers to paying subscribers increases, because you’re doing something that people really find valuable. That’s the promise of his thesis: He’s going to thread that needle and then finds an opportunity to do what he loves, continue working in a field where he’s exceptionally talented, create a livelihood, and serve the public interest by bringing interesting stories to the forefront where they should be.”

For Thomsen, the goal remains the same as it has been his entire career.

“For me,” he says, “it’s really an exercise in having fun and trying to offer people something that they wouldn’t get otherwise. When you realize that the world’s changing, you only have two choices. You can let it move on without you, or you can run alongside, jump on, and try to figure it out.”

How Getting Involved and Leadership Roles in Student and Campus Organizations Led to the Right Graduate School Fit

Danzel Jones graduated in May 2021 with a Master of Professional Studies degree in Digital Media with a concentration in Digital Video. When you count up all the organizations, initiatives and groups that Danzel Jones was involved with during graduate school, you can’t help but be in awe of how he was able to finish his degree in such a timely manner.

While in graduate school, Danzel was President of the Graduate Student of Color Collective. He is the Graduate Program and Events Assistant at the John D. O’Bryant African American Institute assisting with existing and new programming initiatives as well as the operations of the Center. He has also served as one of six student members of Northeastern’s College of Professional Studies Council for Equity, Inclusion, and Diversity Initiatives.

Also, he was honored in April as the Northeastern University Student Leader of the Year during the Student Life Awards given by the Northeastern Center for Student Involvement. In addition, he started Spotlight Media, his own photography and videography business; he has created and posted numerous videos on YouTube. Outside of school and work, his faith is very important to him, and he is very active at the Rehoboth Lighthouse Full Gospel Church Inc. and with the Northeastern University Unity Gospel Ensemble.

Danzel is also cofounder and cofacilitator of Conscious Connections, an interfaith initiative for faculty and staff through the Spirituality Center.

For Danzel, it took time to find the right program, the right fit, timing to join organizations, get involved, work within and then eventually lead these organizations. He also found a way to balance his outside activities and his academics and encourages others to do the same.

“I always made the distinction between quitting and throwing in the towel and I never threw in the towel, said Danzel. Whenever I speak to high school and college students, I make the point of saying — to never throw in the towel.”

When asked why he selected Northeastern, he says that the program didn’t require the GRE (a standardized test for admission to graduate school) and the hands-on and the collaborative approach to learning were key factors in his decision. Danzel also realized that digital media was always his first and foremost interest.

Danzel’s focus on digital media started at the Humanities and Leadership Development campus of Lawrence High School in Massachusetts, where he took production classes. From there, he went on to receive his Associate in Arts degree in Liberal Arts with a concentration in Communication from Middlesex Community College and his Bachelor of Arts in Communication degree from University of Massachusetts Amherst. Before Northeastern, he studied for his master’s degree in Public Administration in West Virginia.

“Some of the work I’m most proud of is expanding BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color) outreach and beginning to establish chapters on regional campuses, connecting with international students and to all students who don’t identify as white,” said Danzel. “I helped students engage during the global pandemic, and conduct conversations in a virtual space, which enabled people to vent about a wide range of issues including family, work and classes.”

Danzel’s thesis advisor and many of his classes were with Lecturer, Gary Greenbaum – who helped shape his capstone and thesis.

“I did a documentary on John D O’Bryant, the first African American to be appointed a Vice President of Student Affairs at Northeastern University and interviewed O’Bryant’s son, Dr. Richard O’Bryant and got his approval for the piece. Some of the classes that were so meaningful to me were about casting calls, and budgeting, as well as grants you can apply for to fund your project.”

What’s next for Danzel? In addition to his work at the John D. O’Bryant African American Institute, Danzel is helping a friend campaign for a School Committee seat in Haverhill, MA, designing the campaign website and photographing events.

After that, maybe it’s divinity school or a doctoral degree; for certain, Danzel will be using digital media to express his ideas.

5 Ways to Improve Your Storytelling on the Web

By Jay Laird.

Jay Laird, a faculty member in the Digital Media Program, co-designed the game design concentration at Northeastern.

You’ve decided on your story. It delivers your message. It’s relevant to your audience. But which is the best way to tell it on the Internet? The web gives us more ability than ever to tailor form and function to best suit our content.

While storytelling is the key to shaping your message, each medium used to tell it has its own tips and tricks to maximize its effectiveness. We teach each of these and more at Northeastern’s College of Professional Studies ‘ Digital Media program.

Here are five ways to improve your storytelling techniques on the web, one for each of the five common elements of web-based storytelling:

1. Photos – Identify Your Character

One way to improve your storytelling through photography is to identify the character of your photos – even if there are no people in it. Compose your shots with an awareness of scale, position and contrast to make sure the subject of your photo not only draws attention, but also conveys some sense of character. Look at the subject and the interplay against the background, or if it’s a person, how he or she is dressed and what he or she is holding. If the audience gets a sense of personality – even if your subject is a light switch – they will pay more attention.

2. Video – Edit, Edit, Edit

The old adage is true: Less really is more. On the web, your audience’s time is limited, so it’s critically important to show only the key moments that establish what you’re trying to say. Get the important bits out up front. Here’s a challenge: Try to convey the core of your message in a six-second Vine!

3. Illustrations – Control the Color Palette

You might have a lot of information that needs to grab the reader’s attention, but don’t use every color in the rainbow to do it. For infographics, a good color palette will contain two to five harmonious colors. Even if you have never taken any design courses, there are a few apps and shortcuts designed to help you here, including Kuler.adobe.com . Select one to two colors based on the mood you’re going for, and let Kuler recommend the others. When working on a project with a team, make sure everyone has agreed on the color palette and the importance of keeping it consistent.

4. Text – Consider Your Heirarchy

The basics of writing for the web are already well-documented. Keep paragraphs short. Take advantage of white space. Use bold subheads and lists as much as possible. But to take your web writing to the next level, establish a viable hierarchy of information that will guide your audience as they scroll through your site. The key here is viable – while it’s a good idea to grab an eye with one or two ideas “above the fold,” you don’t have to tell the whole story within the first screen of your website. More often than not, attempts to cram everything “above the fold” lose readers rather than gaining them. Trust the reader’s curiosity: if you tell people there’s an amazing hamburger below, they’ll scroll down or click for details!

5. Interactivity – Set the Path

Design your interactive elements so the audience can control how quickly and how thoroughly they follow the story. Carefully design your interaction points to lead your audience through the story you want to tell, while still giving them the ability to control the flow of storytelling. Provide leaders with jump-links to skim past items that don’t interest them, but always give them a way to go back. Consider providing sub-pages to give them the ability to go really in-depth before moving on, but be sure they know they have a way back to the main narrative.

4 Ways Games are Improving Scientific Research

Jay Laird, a faculty member in the Digital Media Program, co-designed the game design concentration at Northeastern.

Games are a growing part of our lives, and in more ways than you might think.

Thanks to our mobile devices, we can always kill that few minutes’ wait for a train with a game of Bad Apples. With services like Beeminder we can gamify our day-to-day tasks by betting money on whether we’ll complete them. And with the availability of free educational resources like DuoLingo on our computers, tablets, and phones, we can turn that “one more game” urge into a few minutes or a few hours of foreign language learning.

So games can help us to learn, work and – of course – to kill time, but can they help us to do serious research? Definitely! Here are four ways games are improving scientific research.

1. Crowdsourcing Tough Science Problems

Pattern recognition is a tough problem for computers, but humans are wired for this way of thinking. Two recent examples of scientific crowdsourcing games are EyeWire and Fold-It.

EyeWire challenges players to complete the shapes of complex 3D structures by looking at a series of 2D “slices” to deduce what’s missing. The application? It’s actually a model of neurons in the human brain. If us humans score points, the model of the neuron gets one step closer to completion.

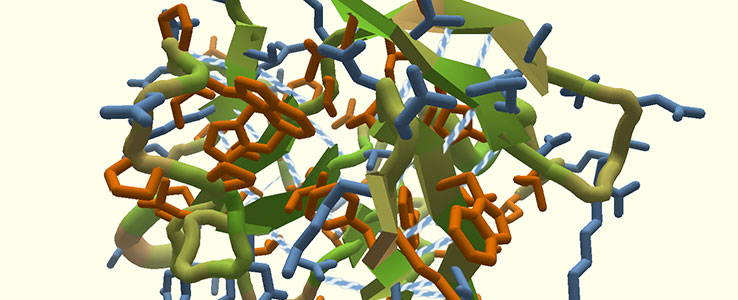

A much more complicated game, Fold-It, challenges players to “fold” proteins into the best possible structure. As the site says, “Figuring out which of the many, many possible structures is the best one is regarded as one of the hardest problems in biology today and current methods take a lot of money and time, even for computers.” As with EyeWire, the human intuition for pattern matching helps the computer in its quest for the ideal solution— which in turn helps scientists to develop drugs to cure diseases.

And did you know you can help scientific research by playing your own games? When using the “Playstation at Home” application on your Playstation 3 or Playstation 4 system, you can donate your game console’s extra computing power to the “cloud” of computers that are working on the Fold-It challenge.

Eye Wire

2. Gathering Data to Advance Behavior/Social Science

The PopCosmo team at University of Wisconsin-Madison investigates learning in online games and in their fan communities. They conduct “naturalistic, survey, and experimental research” into individual and group cognition in games like World of Warcraft, Dragon Age Legends, and the Elder Scrolls universe.

As part of their work, they have used empirical data to compare in-game behavior with in-school behavior among teenage boys who are “disengaged and failing in school,” with a goal of identifying ways of keeping the students engaged in school.

While it’s difficult to observe the individual behaviors of a large population in the real world, in-game behaviors can be recorded automatically, providing a wealth of hard data for social scientists in a short amount of time.

World of Warcraft

3. Gamifying Data Analysis

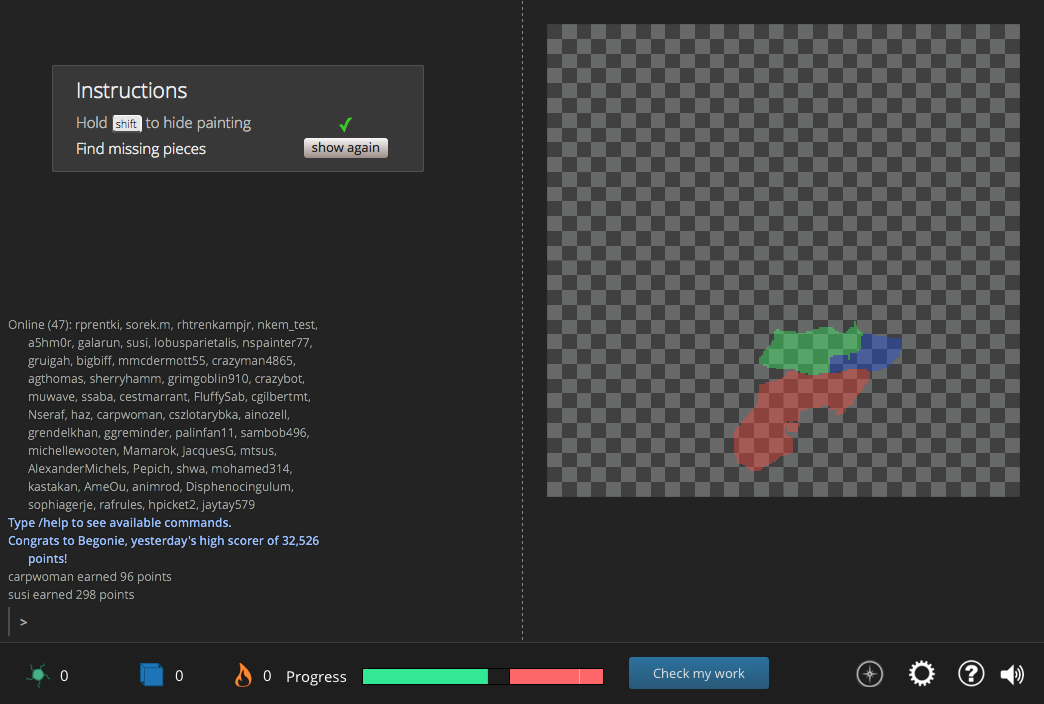

“Gamification” is the addition of game-like features to something that isn’t traditionally a game. Sites like Zooniverse award points and achievements for “players” who assist with data collection and cataloging.

When a Museum of Natural History wanted to digitize its insect collection, the minuscule tags attached to each specimen proved near-impossible for a computer to read, so Zooniverse set its players on the task of decoding the tiny half-century-old scrawls of some of the collectors.

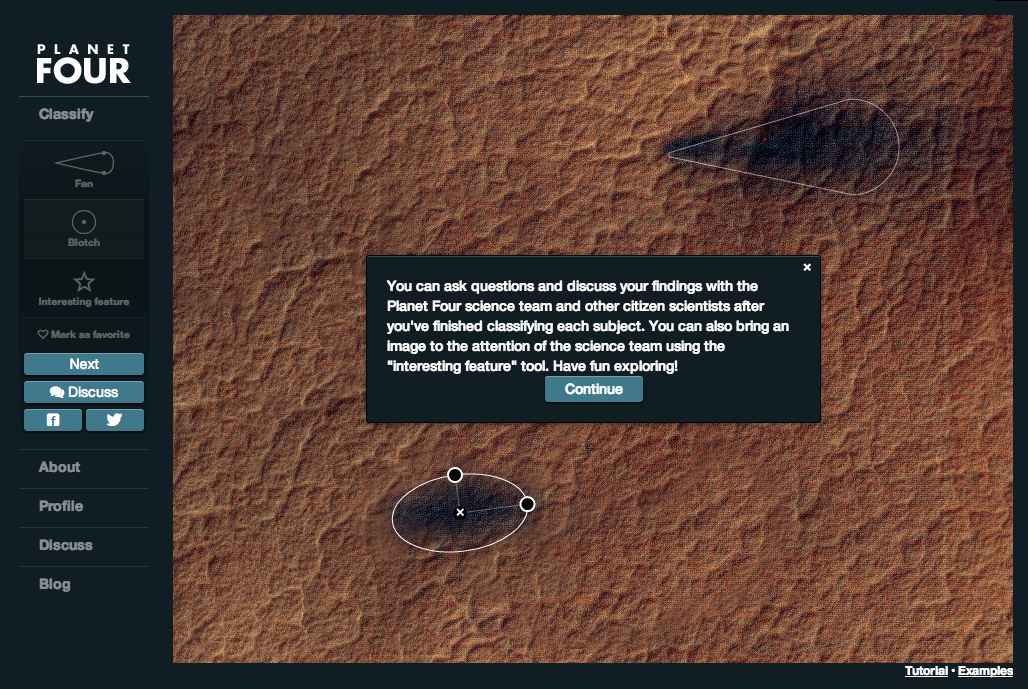

A more recent Zooniverse project, Planet Four asks players to identify features on the surface of Mars and to bring any interesting ones to the attention of the community.

Another data analysis site, TomNod, crowdsources observations a bit closer to home, awarding points for “quests” to find certain features in satellite images of Earth.

With the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, TomNod has focused its players’ efforts on helping to search for the missing aircraft— with so many people eager to help that the site can’t keep up with the traffic.

Planet Four

4. Games as a Direct Research Tool

Finally, there are games that contribute directly to collecting scientific data, including some that we at Northeastern have developed with funding support from the National Science Foundation: Shortfall and Geckoman.

These games teach students about science, but they serve an additional purpose: to contribute data to research about how students learn.

“Shortfall” lets students explore different paths towards environmentally benign manufacturing while competing as various companies in the automobile industry. Students set their own sustainability goals— do they define success as financial, social, or environmental, or an even amount of each?— and then play to reach those goals. By observing each student’s play style, we hope to tailor the game material to challenge their individual assumptions so that they will learn something new with each round of the game.

With “ Geckoman,” we have created a game that teaches elementary and middle-school kids some key concepts behind nanotechnology while they play a fun, cartoony scrolling platformer. Through the GAMES Initiative, we are adding features to Geckoman to discover how much videogame-based science learning involves trial-and-error versus reading and applying knowledge.

Geckoman

5 Ways to Strengthen your Message through Storytelling

Jay Laird, a faculty member in the Digital Media Program, co-designed the game design concentration at Northeastern.

It’s tempting to think that the modern technology we have at our disposal is all we need to deliver a killer message to our audiences.

But the key to delivering an idea or message effectively lies in an ancient art: Storytelling.

Storytelling reinforces your message by establishing an emotional connection with your audience. It helps people to better comprehend your ideas. It shows who you are. And it’s one of the elements at the very center of Northeastern’s Digital Media program in the College of Professional Studies.

Here are five ways make your message stick by improving your storytelling techniques:

1. Choose the right medium

There’s photo, video, infographics and interactivity — and many means of delivery for each medium. Instead of feeling paralyzed by options, consider which one best conveys your story. Video is great for showing a linear process, while an infographic is ideal for letting people explore information change over time. Photos (subjects and backgrounds) are worth a thousand words, but plain text is better if you want your audience to conjure a mental picture they identify with. And your audience may have a lower or higher trust level for some mediums versus others.

2. Begin your story with characters.

Let’s say there’s a problem, and your brand or idea is the solution. Even though it may be your first instinct to present your solution, it may be obvious to you that your solution is the best one, your audience may need a bit more convincing. Or, even if they believe you, they may not remember your message later.

Develop a character who would have the same kind of problem that you’re trying to solve. If your audience identifies with the character or at least sympathizes with him or her, they will recall more details about your message or idea and they will be more likely to connect it to other aspects of their lives later on.

3. Identify the problem.

The most common dramatic structure of a story is to give a character a problem and then make him struggle find a solution. Whether you’re doing a 30-second commercial or an hour-long lecture, start off by letting the audience know why they should stick around until the end.

You might even create a certain amount of suspense, causing the audience to wonder how the problem will be solved, or even if it will be solved. Can the family displaced by a flood find a place to stay for the night? Will that dirty kitchen get cleaned before the judgmental father-in-law shows up?

4. Take a journey to the solution, together.

When your characters take the audience on their journey, your audience connects the problem to the solution and better remembers both.

Maybe it’s something trivial like cleaning the kitchen or something agonizing like facing the prospect of being homeless, but in both cases, you increase the audience’s engagement by raising the stakes and making them eager to find out if everything will turn out okay.

This isn’t to say that your story has to end happily. To call your audience to action, you might instead illustrate the consequences of the solution not being reached, while offering hope for the future.

5. Use the small story to tell the big story.

Your characters take the audience on the journey from problem to solution, but you need to make sure that the audience takes away some sense of the bigger picture. Maybe it’s not as straightforward as providing a moral in the style of Aesop’s fable, but it needs to be something that connects your story to the world-at-large. If people start seeing elements of your story in their daily lives, they will remember it, and your message. Our memories like to keep things simple, so people usually remember the key elements of the story—the main character, problem, and solution— and then distort the rest over time to support other existing or new memories.

Stories can change perceptions.

Politicians tell anecdotes about some (often imaginary) person they met on the campaign trail like “Joe the Plumber” in the hopes that people will identify with this everyday person and say “Hey, if this candidate connected with Joe, surely he’ll look out for my best interests!” If you can tell the story of a specific man but make people identify with him as an Everyman, then people will start seeing your story as part of the bigger picture of their lives.

Tracking Effectiveness

Of course, crafting the story the story is only the first step. Make sure you test your story. Try telling it in a few different styles or with a few different characters or even though a variety of media. And remember: storytelling began as an interactive medium, an oral tradition in which the audience would often ask questions and change the flow of the story. Even if you’re giving a lecture or showing a video, let your audience know that you are open to feedback. Find out what your audience is taking away from the story. Is it what you expected? Is it helpful in reaching your goals?

Now tell us: What are some of the best examples of brand-based storytelling that you’ve seen?

How to Build Your Own Interactive Content for the Classroom

By Gail Matthews-DeNatale, PhD.

Gail Matthews-DeNatale, PhD, is a faculty member in Northeastern’s College of Professional Studies graduate education degree programs. She specializes in eLearning and Instructional Design.

If your courses include any sort of online components, whether it’s a full-blown online course or a a small-time discussion board, you’ll need to learn to create interactive content to keep your students learning when you’re not in a physical classroom.

The most traditional choice for teachers are Learning Management System (LMS), but there are also other online tools. Let’s take a look at each.

Learning Management Systems

Most colleges and universities provide Learning Management Systems, which are the Swiss Army knives of online teaching.

They’re an online space in which the teacher can develop course websites that include both content and a range of tools for interactive learning, such as threaded discussions, live web-based conferencing, group work space, and collaborative authoring spaces (such as wikis).

The most popular LMSs in higher education are:

Edmodo is another LMS-like tool that’s frequently used in K-12 settings.

Many of these are only available through institutional licensing, but some, like Canvas and Edmodo, provide free accounts for those who are interested in using them on a small scale. A number of them have launched handy mobile apps.

Pros: Both licensed and free LMSs can be wonderful options for creating an integrated learning environment that provides both variety and continuity.

Cons: A full-featured LMS takes time to learn, and because your course content becomes embedded in the system, it’s cumbersome to switch to another LMS if a new and better one comes along.

Other Online Tools

If you’re in a face-to-face setting and want to augment your students’ learning experience, consider using products such as the Google Suite. Google Drive makes it possible to share files and author materials collaboratively, and Hangouts works well as a web-conferencing tool with an “on air” option in which live sessions can be recorded and exported to YouTube. You can even create surveys with Google Forms.

VoiceThread is one of the most popular tools for creating online conversations around presentations. You can upload a presentation, use a microphone or telephone to record the audio, and can even set it up so that viewers can comment on and annotate the slides.

SlideShare is a user-friendly tool for sharing and organizing presentations online and it can be embedded in social networking sites such as LinkedIn. In addition, many educators create a Twitter hashtag for their courses and use that as a method for engaging students in quick bursts of communication and resource sharing.

Pedagogy Wheel maps dozens of cutting-edge tools to learning scenarios. I encourage you to use it as tool for decision-making on how to use technology to support learning. The Pad Wheel helps all of us keep our focus on the forms of learning engagement that matter most: remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating.

Pros: These “light weights” tend to be more attuned to the conventions of social media, providing a user-friendly, media-rich, and socially interactive learning experience. They’re also tools that we use in other aspects of our lives every day, so they break down the barriers between school and the rest of life.

Cons: Because these tools are free and on the cutting edge they also come and go in a moment’s notice. It’s important to avoid basing your entire course on one app. In addition, there are so many creative, free tools available online that it’s easy to get tool-happy and lose sight of your true goals.