Student Matthew Cardona presents the Northeastern team’s finding at Draper Laboratory in Cambridge, MA.

Using remote sensing technology, Professor Cordula Robinson and a team of students begin the virtual excavation of what appears to be a new Mayan site in Guatemala.

It all started with a visit to the family farm. In the summer of 2014, Matthew Cardona, now a master’s student at Northeastern’s College of Professional Studies Geospatial Services program, had just graduated from the University of Scranton in Pennsylvania. As a graduation gift, his parents bought him a ticket to Guatemala. His father had grown up there, rambling through the oddly shaped hills and playing with the fragments of pottery and jade that littered the landscape. Matthew, who was raised in Marlborough, Mass., had visited some historic sites on a school trip to Guatemala, but he had never been to see his family’s ancestral home in the country’s rural southeast.

One of a number of relics that have been unearthed near the Cardona family homestead in Guatemala.

The morning after his flight landed, Cardona says, he had woken up early and begun to explore the farm when somebody called him over to a dusty shed. Inside, he found a mystery.

“The walls were lined with all these boxes,” Cardona says. “Inside were all these artifacts that had been recently dug up. I got to see them the day before they were moved off to an undisclosed site, and I sat down and I started taking photographs. I kept them secret, but I kept it always in the back of my mind.”

Three years later, Cardona was living back in Boston, working the evening shift as a security guard at Draper Laboratories in Cambridge, Mass. Long nights running bags and briefcases through an X-ray scanner had convinced him he wanted to improve his prospects by continuing his education. An enthusiasm for foreign policy, history, and computer games of global strategy, such as Advance Wars and Sid Meier’s Civilization 4, had prompted him to set his sights on geospatial research and intelligence gathering. Rather than guarding the entrance to the renowned research laboratory, Cardona dreamed of working upstairs as a researcher in his own right. When he learned that Draper had a tuition-reimbursement program, he started learning about different schools.

“I looked up Northeastern,” Cardona says. “I saw [Teaching Professor Dr. Cordula Robinson]. I saw her program with archaeology. I always was really curious about what had been found [near] my family in Guatemala, so I decided to take that route.”

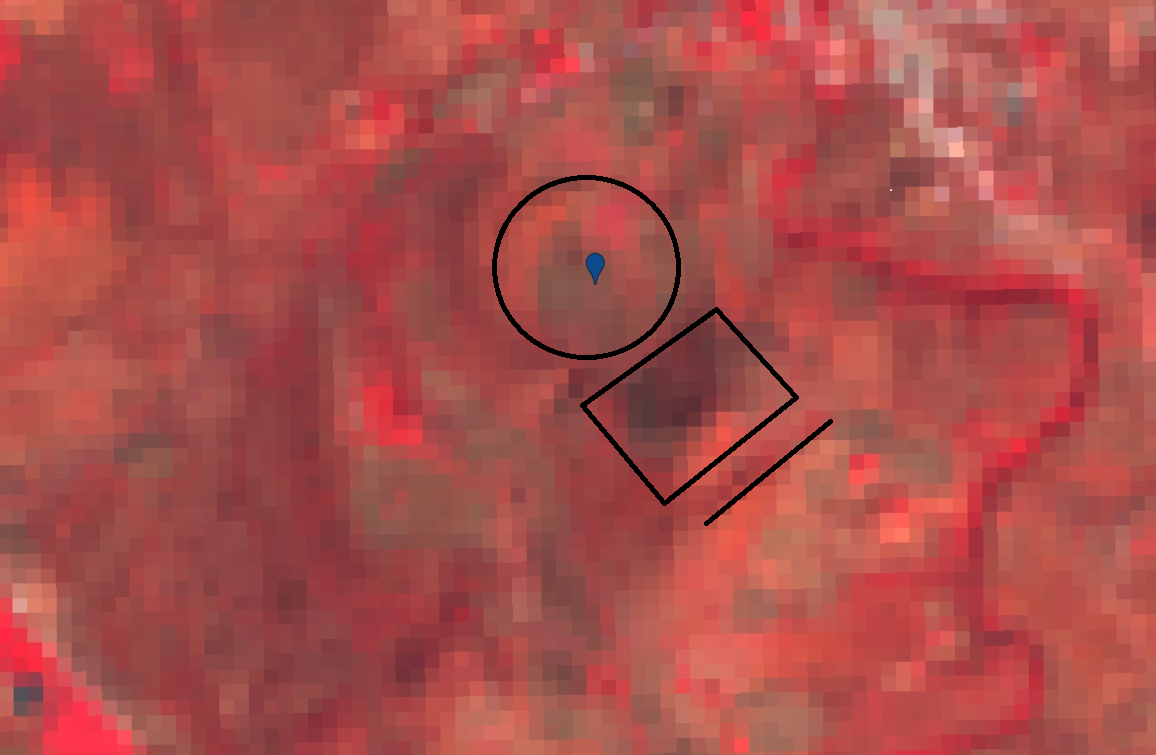

Students used remote sensing technology to uncover Mayan ruins in Guatemala.

In January of 2018, Cardona remembers sitting with his laptop, staring at satellite imagery of his father’s hometown in Guatemala. Through the course he was by then enrolled in with Robinson—“Remote Sensing for Archaeology,” a class she had created—he was using software that allowed him to visualize the surface of the earth based on soil composition. As he surveyed the area for clay, a foundational Mayan building material, gigantic shapes began to emerge before his eyes: circles, pyramids, rectangles and squares.

“I realized,” Cardona says, “that they were buildings … buried underneath the ground.”

He showed his professor, who was intrigued, but cautious.

“Matt got really excited,” Robinson says, “and he stoked my interest with the degree of his enthusiasm. It’s so much excitement and enthusiasm you could almost bottle it—or want to. And he just went full-steam ahead saying that he’d found something.”

Nevertheless, she says, “He had [only] one piece of evidence, and I wasn’t convinced.” Another problem was that Cardona wasn’t sure how to reproduce his results.

But there was enough there that Robinson agreed to help Cardona test his theory. To complete the team, she recruited Rebecca Greber and Elizabeth Krueger, also students in the program with experience in archaeology and technology, and over the summer she guided the three students through an independent study that entailed a systematic survey of the landscape—using an array of geospatial imaging techniques—as well as a rigorous literature review and a scholar’s bootcamp on the standards for publishing an academic paper.

In the course of their work, Greber and Krueger caught some of Cardona’s enthusiasm and gained deeper insight into the technologies available for archaeological exploration.

“One of the things I was surprised by is how much information there is even in lower spatial resolution datasets,” Krueger says. “While we did end up getting access to high-res imagery from the Digital Globe Foundation later on, a lot of the work used 10- or 30-[meter] resolution images, and even though that wouldn’t show as crisply [in terms] of details, it was fine enough to let us analyze patterns in things like elevation and soil composition that were helpful for trying to figure out what might have been man-made versus natural features.”

As they dug into the data together, the team soon built a sense of camaraderie. “I have really enjoyed the incredible collaboration,” Greber says, “the effort Professor Robinson put in to get us access to data and encourage us to focus on this particular thing and save other questions for later—providing very wise guidance, as we could get so enthused about all of it as to be brought to a standstill. And, especially, Matt’s overwhelming enthusiasm about this site and desire to help the people there.”

By the end of the summer, combining geospatial search tools with electromagnetic-wavelength and soil-composition filters Dr. Robinson had customized using the JavaScript programming language, the students had accumulated enough data to persuade even their professor.

“I think we’ve got really good evidence that is totally worth a trip there,” Robinson says. “I feel quite sure that some of these areas are Mayan.”

For her students, the success was thrilling.

The team of Geographic Information students with Professor Cordula Robinson (pictured second from right).

“It was an amazing feeling when we actually did find what look like very valid places for further investigation,” Greber says.

Though they aren’t the first to use remote sensing to find new archaeological sites—a study published in the September issue of the journal Science details the results of a 2016 survey that found more than 60,000 new sites in Guatemala—Robinson believes this may be the first time that the widely available Google Earth Engine, a planetary-scale platform for Earth science data and analysis, has been used with coded filters for this area with such success.

“Google Earth Engine is a relatively new, multi-petabyte, cloud-hosted satellite data resource, including for archaeological applications,” she says. “And all of the students in this class are familiar with it. They’ve taken two classes with me and this independent study, and have good experience in these approaches, as well as automated feature extraction. Combined, it’s a new way of looking at things archaeologically, and maybe we are finding a new path to doing this.”

Robinson says much will depend upon the reception of the paper she and her students have authored, which “is asking for rigorous and reputable and repeatable techniques using remote sensing for archaeology.” The fact is, she says, “that [Google Earth Engine] is this huge repository of information and that I can feasibly share my code—you know, we can share that code and people can check. So, we’ll see.”

Cardona—who presented the team’s findings at his employer, Draper Labs, in October—says that if the opportunity arises to return to Guatemala, he’ll be ready.

“I want to go down there,” he says. “That’s my dream. The number of sites … has barely been scratched.”

He has also enjoyed shared the findings with his family.

“They’re stunned,” he says. “They grew up in the shadow of giants and had no clue.”